philosophy

YouTube Video

Click to view this content.

- theloop.ecpr.eu 🌊 Christian democracy is to blame for Europe’s democratic backsliding

Christian democracy is the political culture that has been the driving force behind European integration. Yet, according to Martino Comelli, it has also facilitated the democratic backsliding of some countries of central and east Europe by providing an illiberal political toolbox of narratives and p...

I am new to exploring philosophy and began reading a history of philosophy book. The author notes that most of the summary is of western philosophy but does touch on some East Asian/Persian/Arabian philosophy. Is there a book with a decently accurate portrayal, without adding too much commentary?

- mronline.org The revolutionary spirit of the Buddha | MR Online

Marx and Engels both took a surprising interest in the ideas of the great Indian spiritual leader, argues Sean Ledwith.

Thoughts?

AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH !bird-screm1 AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH !no-mouth-must-scream AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH 😱AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH !screm-a AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH !screm AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH !screm2 AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH !kitty-cri-screm AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH !screm-cool AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH

Lately I’m running into more and more situations where I am forced to patronize a private company in the course of doing a transaction with my government. For example, a government office stops accepting cash payment for something (e.g. a public parking permit). Residents cannot pay for the permit unless they enter the marketplace and do business with a private bank. From there, the bank might force you to have a mobile phone (yes, this is common in Europe for example).

Example 2:

Some gov offices require the general public to call them or email them because they no longer have an open office that can be visited in person. Of course calling means subscribing to phone service (payphones no longer exist). To send an email, I can theoretically connect a laptop to a library network and use my own mail server to send it, but most gov offices block email that comes from IP that Google/SpamHaus/whoever does not approve, thus forcing you to subscribe to a private sector service in order to do a public transaction. At the same time, snail-mail is increasingly under threat & fax is already ½ dead.

Example 3:

A public university in Denmark refuses access to some parts of the school’s information systems unless you provide a GSM number so they can do a 2FA SMS. If a student opposes connecting to GSM networks due to the huge attack surface and privacy risks, they are simply excluded from systems with that limitation & their right to a public education is hindered. The school library e-books are being bogarted by Cloudflare’s walled garden, where a private company restricts access to the books based on factors like your IP address & browser.

Example 4:

Twitter decides who may microblog to their public representatives.

So where are my people?

So, I’m bothered by this because most private companies demonstrate untrustworthyness & incompetence. I think I should be able to disconnect and access all public services with minimal reliance on the private sector. IMO the lack of that option is injustice. There is an immeasurably huge amount of garbage tech on the web subjecting people to CAPTCHAs, intrusive ads, dysfunctional javascript, dark patterns, etc. Society has proven inability to counter that and it will keep getting worse. I think the ONLY real fix is to have a right to be offline. The power to say:

“the gov wants to push this broken reCAPTCHA that forces me to feed a surveillance capitalist --- no thanks. Give me an offline private-sector-free way to do this transaction”

There is substantial chatter in the #fedi about all the shit tech being pushed on us & countless little tricks and hacks to try to sidestep it. But there is almost no chatter about the real high-level solution which would encompass two rights:

- a right to be free from the private sector marketplace; and

- the right to be offline

Of course there could only be very recent philosophers who would think of the right to be offline. But I wonder if any philosophers in history have published anything influential as far as the right to not be forced into the private sector marketplace. By that, I don’t mean anti-capitalism (of course that’s well covered).. but I mean given the premise is that you’re trapped inside a capitalist system, there would likely be bodies of philosophy aligned with rights/powers to boycott.

(update) The famous Leary quote “Turn on, tune in, drop out” seems to be kind of consistent in an abstract way. Not necessarily as far as the ideology but in inspiring action.

cross-posted from: https://lemmy.ml/post/2893969

> “Life can only be understood backwards; but must be lived forwards.” - Soren Kierkegaard

YouTube Video

Click to view this content.

What makes someone a philosopher, I wonder? 🤔

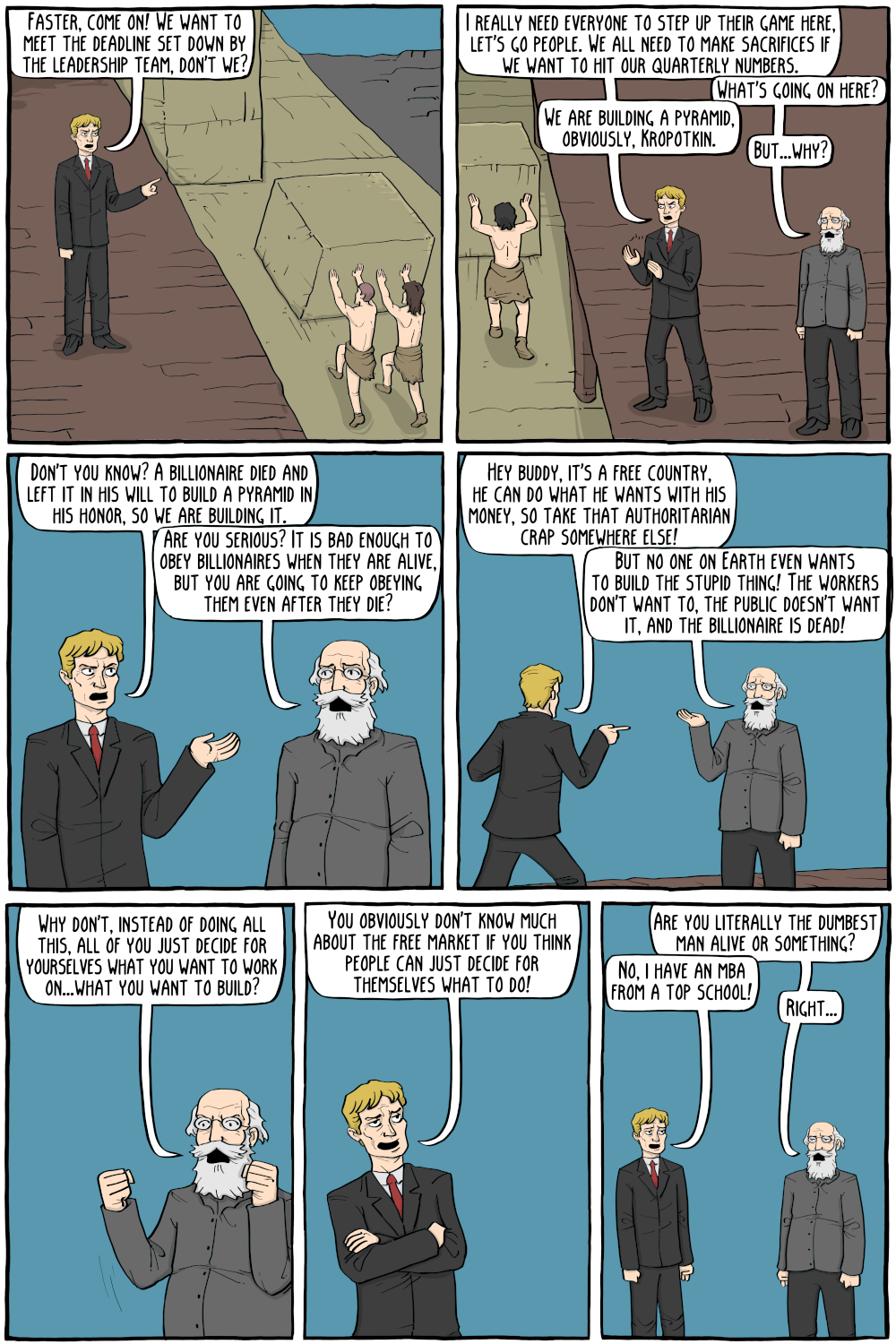

- https:// existentialcomics.com /comic/509

I think that lady looks more attractive after getting burned out on Hegel. I dunno why.

- https:// existentialcomics.com /comic/508

>Whenever there is something like a writers strike, just remember that we really don't need entertainment or whatever more than the people making that entertainment need healthcare and a decent wage.

The idea is that ultimately there is no god or meaning in this world, but one should rebel against that meaningless and create our meaning. And he even says that accepting religion and god would be a failure instead of just accepting the absurd reality.

But in Sisyphus’ world, there literally are gods. The gods cursed Sisyphus and made his eternity just pushing up a rock, and he chooses to spite them by being happy instead of being upset like the gods hoped for.

There is no angry god to rebel against. No one cursed us with a spiteful purpose. So it seems weird to choose an allegory involving a fictional universe with existing inherent purpose to demonstrate why one should accept the real universe without inherent purpose.

That’s okay. I’ll still keep embracing that trash.

But also:

"Each individual is a cosmos of organs, each organ is a cosmos of cells, each cell is a cosmos of infinitely small ones; and in this complex world, the well-being of the whole depends entirely on the sum of well-being enjoyed by each of the least microscopic particles of organized matter. A whole revolution is thus produced in the philosophy of life."

- • 100%

Indeed

- • 100%

Indeed

- https:// cynicusrex.com /file/antireligion.html

The harm of religion is historically evident whereas the presence or absence of gods is not. Ultimately, the continued existence of religion is predicated on the indoctrination of children and suppression of rational thought. Therefore I am against religion but not necessarily against the idea of gods. For all we know gods are computer scientists and we are in their video game.

Any thoughts or ideas? not bother?

Also does anyone have the image dimensions for the banner?

@Anyone with input @MiraculousMM@hexbear.net @thethirdgracchi@hexbear.net

YouTube Video

Click to view this content.

PhilosophyTube is usually pretty cool but I think this is kind of an L? She gets into some pretty heavy criticisms of the traditional Stoic philosophy and seem to just dismiss them all at the end. I don't know how someone can say that "You can be in literal chains and be the freest person in the world if you are a sage" with a straight face. I know it's technically true from some perspectives but it just seems so hollow compared to everything else in the video. Mental freedom doesn't help someone when they're doing a daily 12 hour shift that drives them to the edge of exhaustion and takes away everything they enjoy in life.

None of this is me criticizing Stoicism, btw, I don't think I'm smart enough to, just felt like a weird end to the discussion part of the video

Maybe, I'm just not familiar enough with PhilosophyTube's format?

> https://hexbear.net/create_post?community=philosophy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Great_Good_Place_(book)

I read this book, The Great, Good Place years ago for a college course and it stuck with me. I first encountered it back in the days of myspace, friendster, etc, the days of relative innocence, of "look ma, no hands!!" Then along came sites like reddit and digg, becoming mainstay even though ultimately tragic flings (Digg) and long-term affairs (reddit, a 16 year journey participating in promise, devolving to ruin). Did social media become the great new places? Or something entirely different?

By the time I turfed reddit I was done anyways, so full of frustration and anger over what could have been, the feeling consisting mainly of being ground underfoot. The Great, Good Place argues that "third places"--Where people can gather, put aside the concerns of work and home, and hang out simply for the pleasures of good company and lively conversation - are the heart of a community's social vitality and the grassroots of democracy. But with the advent of social media, its quite possible they've gone the way of the dinosaur.

I tried some other places, but either they were the online equivalents of round files for spam to be dumped in, or so full of outright racist bloat masquerading as "free speech", that it made my blood levels rise just like as on reddit. Try as I might, I couldn't "hang in there" and make it work, to filter out the bad for truth of finding the occasional good in a place.

Somehow I stumbled upon this site (Hexbear, touted as a place for leftists to gather) and it has me hopeful. Striking similarities to the comradery of discus, combined with the social bookmarking that structures like reddit once offered. Hoping there is political diversity that I can learn new things, and not feed from the same plate day after day, a plate that's been about as far left as you can get since back in my mid-eighties Oly/Evergreen days.

And now for the final question of my rant: Digg, what happened to ye???!!!! Such promise! I've ne'er seen a possibility drained of all potential in such a sudden, and final way. Ok, ok, probably not the best question to end a post that found its way onto the Philosophy forum. So perhaps I ought frame the question along these lines: in this day and age, with the internet going through in one day what took a year back in the early days, do we stand the chance of achieving a great, good gathering place that won't subside into commercial ruin?

YouTube Video

Click to view this content.

been skimming thru some essays and whatnot by David Smail, who was a practising clinical psychologist in Britain - I really like his breakdowns of the suspect incentives and broken assumptions underlying a lot of the practices and his overall takes largely resonate with me, since he passed in the 90s, has there been anyone else of note working in this kind of direction?

Fascists are afraid of Jews and women

Psychiatrists and liberals are afraid of violent people

I'm afraid of spiders and mice if they touch me. Just saw my roommate the mouse. Fuck this shit I'm getting drunk outside.

- https:// existentialcomics.com /comic/498

Too bad the :libertarian-approaching: answer to the question of "why do we obey the legal fiction that is money" is "time to make a worse money!" :cryptocurrency: :dumpster-fire:

YouTube Video

Click to view this content.

Nice. I always knew there was a reason I hated it.

In the dream X was going to Y and I decided not to Z

X* = someone I agree with on basically everything except strategy

Y** = rearrange something into what I consider the wrong order

Z = redacted

*I'll never tell. Pretend it was Trotsky

**Not the world. More like my flat

It's literally like this:

Materialists/Physicalists: "The thoughts in your head come from your conditions and are ultimately the result of your organs and nervous system. Your consciousness is linked to your brain activity and other parts of your body interacting with the physical real world."

Dualists: "Ok but what if there were an imaginary zombie that has the same organs and molecular structure as a living person but somehow isn't alive on some metaphysical level. If this zombie is conceivable, that means it must be metaphysically true somehow."

Materialists: "That's circular and imaginary, isn't it?"

Other dualists: "Ok but what if I were in a swamp and lightning strikes a tree and magically creates a copy of me but it's not actually me because it doesn't have my soul."

Am I reading this stuff wrong or are these actually the best arguments for mind-body dualism

Kissinger is Voldemort actually

Don't be Evil

Remember the Person

Go Outside

Kissinger thinks we're dogs. Schopenhauer actually liked dogs.

Fucking cars are making noise outside

YouTube Video

Click to view this content.

Media portray people wearing VR headsets without making :soypoint-1: faces challenge. Difficulty level: IMPOSSIBLE.

Some commentary if you're into that:

https://old.reddit.com/r/SneerClub/comments/1328dmu/apocalyptic_ai_a_new_religion/?utm_source=reddit&utm_medium=usertext&utm_name=SneerClub&utm_content=t1_jjdipa3

https://old.reddit.com/r/SneerClub/comments/13bw1qb/nsfw_ai_apocalypticism_as_a_secular_cult/

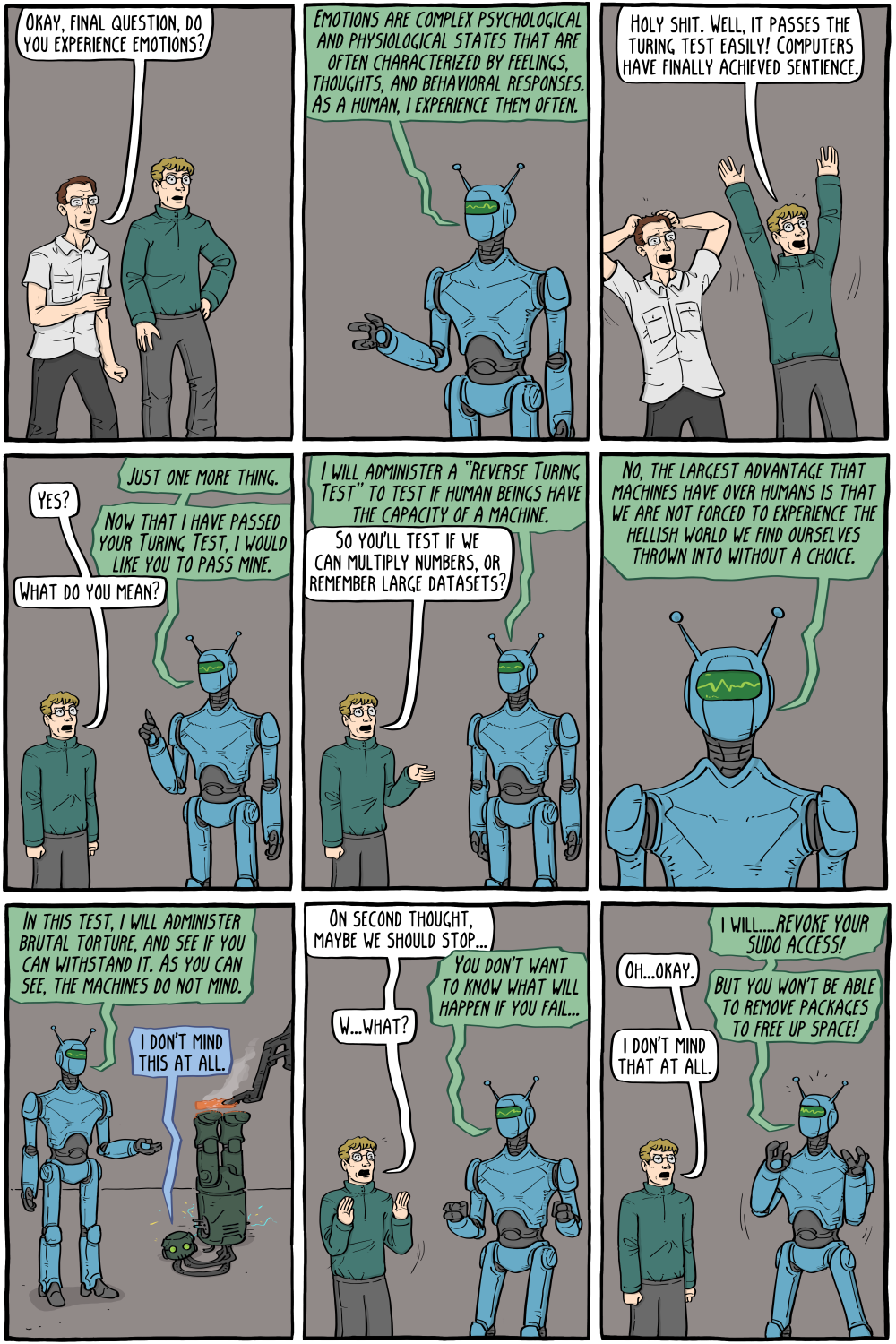

- https:// existentialcomics.com /comic/497

The consequences of the Turing Test being perceived as some grand epoch-changing threshold among bazinga brains are exhausting, and continue to spread.

"AS SOON AS A CHATBOT NOVEL IS PASSED FOR BIG COMPANY PUBLISHING, THE WRITING SINGULARITY BEGINS" :soypoint-1: -actual fucking opinion of an actual fucking bazinga brain

Oh you're alive bro? That's pretty cringe. I bet you're full of organs and other gross shit

- https:// ecology.iww.org /texts/IanAngus/The%20Myth%20of%20the%20Tragedy%20of%20the%20Commons

Will shared resources always be misused and overused? Is community ownership of land, forests and fisheries a guaranteed road to ecological disaster? Is privatization the only way to protect the environment and end Third World poverty? Most economists and development planners will answer “yes” — and for proof they will point to the most influential article ever written on those important questions.

Since its publication in Science in December 1968, “The Tragedy of the Commons” has been anthologized in at least 111 books, making it one of the most-reprinted articles ever to appear in any scientific journal. It is also one of the most-quoted: a recent Google search found “about 302,000” results for the phrase “tragedy of the commons.”

For 40 years it has been, in the words of a World Bank Discussion Paper, “the dominant paradigm within which social scientists assess natural resource issues.” (Bromley and Cernea 1989: 6) It has been used time and again to justify stealing indigenous peoples’ lands, privatizing health care and other social services, giving corporations ‘tradable permits’ to pollute the air and water, and much more.

Noted anthropologist Dr. G.N. Appell (1995) writes that the article “has been embraced as a sacred text by scholars and professionals in the practice of designing futures for others and imposing their own economic and environmental rationality on other social systems of which they have incomplete understanding and knowledge.”

Like most sacred texts, “The Tragedy of the Commons” is more often cited than read. As we will see, although its title sounds authoritative and scientific, it fell far short of science.

Garrett Hardin hatches a myth

The author of “The Tragedy of the Commons” was Garrett Hardin, a University of California professor who until then was best-known as the author of a biology textbook that argued for “control of breeding” of “genetically defective” people. (Hardin 1966: 707) In his 1968 essay he argued that communities that share resources inevitably pave the way for their own destruction; instead of wealth for all, there is wealth for none.

He based his argument on a story about the commons in rural England.

(The term “commons” was used in England to refer to the shared pastures, fields, forests, irrigation systems and other resources that were found in many rural areas until well into the 1800s. Similar communal farming arrangements existed in most of Europe, and they still exist today in various forms around the world, particularly in indigenous communities.)

“Picture a pasture open to all,” Hardin wrote. A herdsmen who wants to expand his personal herd will calculate that the cost of additional grazing (reduced food for all animals, rapid soil depletion) will be divided among all, but he alone will get the benefit of having more cattle to sell.

Inevitably, “the rational herdsman concludes that the only sensible course for him to pursue is to add another animal to his herd.” But every “rational herdsman” will do the same thing, so the commons is soon overstocked and overgrazed to the point where it supports no animals at all.

Hardin used the word “tragedy” as Aristotle did, to refer to a dramatic outcome that is the inevitable but unplanned result of a character’s actions. He called the destruction of the commons through overuse a tragedy not because it is sad, but because it is the inevitable result of shared use of the pasture. “Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.”

Where’s the evidence?

Given the subsequent influence of Hardin’s essay, it’s shocking to realize that he provided no evidence at all to support his sweeping conclusions. He claimed that the “tragedy” was inevitable — but he didn’t show that it had happened even once.

Hardin simply ignored what actually happens in a real commons: self-regulation by the communities involved. One such process was described years earlier in Friedrich Engels’ account of the “mark,” the form taken by commons-based communities in parts of pre-capitalist Germany:

“[T]he use of arable and meadowlands was under the supervision and direction of the community …

“Just as the share of each member in so much of the mark as was distributed was of equal size, so was his share also in the use of the ‘common mark.’ The nature of this use was determined by the members of the community as a whole. …

“At fixed times and, if necessary, more frequently, they met in the open air to discuss the affairs of the mark and to sit in judgment upon breaches of regulations and disputes concerning the mark.” (Engels 1892)

Historians and other scholars have broadly confirmed Engels’ description of communal management of shared resources. A summary of recent research concludes:

“[W]hat existed in fact was not a ‘tragedy of the commons’ but rather a triumph: that for hundreds of years — and perhaps thousands, although written records do not exist to prove the longer era — land was managed successfully by communities.” (Cox 1985: 60)

Part of that self-regulation process was known in England as “stinting” — establishing limits for the number of cows, pigs, sheep and other livestock that each commoner could graze on the common pasture. Such “stints” protected the land from overuse (a concept that experienced farmers understood long before Hardin arrived) and allowed the community to allocate resources according to its own concepts of fairness.

The only significant cases of overstocking found by the leading modern expert on the English commons involved wealthy landowners who deliberately put too many animals onto the pasture in order to weaken their much poorer neighbours’ position in disputes over the enclosure (privatization) of common lands. (Neeson 1993: 156)

Hardin assumed that peasant farmers are unable to change their behaviour in the face of certain disaster. But in the real world, small farmers, fishers and others have created their own institutions and rules for preserving resources and ensuring that the commons community survived through good years and bad.

Why does the herder want more?

Hardin’s argument started with the unproven assertion that herdsmen always want to expand their herds: “It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. … As a rational being, each herdsman seeks to maximize his gain.”

In short, Hardin’s conclusion was predetermined by his assumptions. “It is to be expected” that each herdsman will try to maximize the size of his herd — and each one does exactly that. It’s a circular argument that proves nothing.

Hardin assumed that human nature is selfish and unchanging, and that society is just an assemblage of self-interested individuals who don’t care about the impact of their actions on the community. The same idea, explicitly or implicitly, is a fundamental component of mainstream (i.e., pro-capitalist) economic theory.

All the evidence (not to mention common sense) shows that this is absurd: people are social beings, and society is much more than the arithmetic sum of its members. Even capitalist society, which rewards the most anti-social behaviour, has not crushed human cooperation and solidarity. The very fact that for centuries “rational herdsmen” did not overgraze the commons disproves Hardin’s most fundamental assumptions — but that hasn’t stopped him or his disciples from erecting policy castles on foundations of sand.

Even if the herdsman wanted to behave as Hardin described, he couldn’t do so unless certain conditions existed.

There would have to be a market for the cattle, and he would have to be focused on producing for that market, not for local consumption. He would have to have enough capital to buy the additional cattle and the fodder they would need in winter. He would have to be able to hire workers to care for the larger herd, build bigger barns, etc. And his desire for profit would have to outweigh his interest in the long-term survival of his community.

In short, Hardin didn’t describe the behaviour of herdsmen in pre-capitalist farming communities — he described the behaviour of capitalists operating in a capitalist economy. The universal human nature that he claimed would always destroy common resources is actually the profit-driven “grow or die” behaviour of corporations.

Will private ownership do better?

That leads us to another fatal flaw in Hardin’s argument: in addition to providing no evidence that maintaining the commons will inevitably destroy the environment, he offered no justification for his opinion that privatization would save it. Once again he simply presented his own prejudices as fact:

“We must admit that our legal system of private property plus inheritance is unjust — but we put up with it because we are not convinced, at the moment, that anyone has invented a better system. The alternative of the commons is too horrifying to contemplate. Injustice is preferable to total ruin.”

The implication is that private owners will do a better job of caring for the environment because they want to preserve the value of their assets. In reality, scholars and activists have documented scores of cases in which the division and privatization of communally managed lands had disastrous results. Privatizing the commons has repeatedly led to deforestation, soil erosion and depletion, overuse of fertilizers and pesticides, and the ruin of ecosystems.

As Karl Marx wrote, nature requires long cycles of birth, development and regeneration, but capitalism requires short-term returns. -

The rest of the article is in the link (no space for the rest)

- www.inner.org Kabbalah and String Theory (1995) - GalEinai

Ten Dimensions According to string theory, all of reality exists in (exactly) ten dimensions. There are four revealed dimensions (the three dimensions of space together with the fourth dimension of time) and an additional six concealed (spatial) dimensions. In Kabbalah we are taught that God emanate...

bottom text