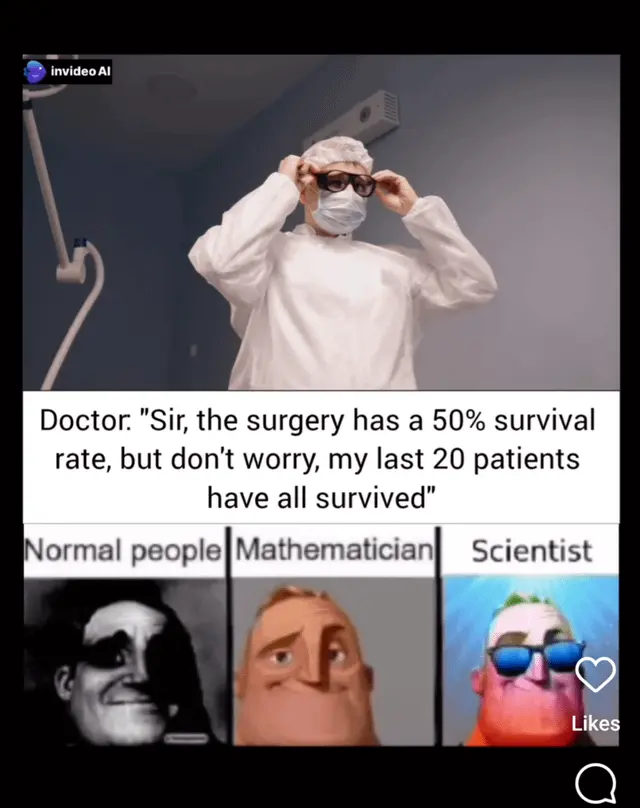

50% survival rate

50% survival rate

50% survival rate

"You should know that 9 out of 10 people who undergo this surgery will die. But don't worry, the last 9 people who took this surgery all died, so you're in the clear!"

😱😱😱

Technically 1 out of 1 people who undergo that procedure die, eventually. Same is true for people who elect not to have the procedure done, eventually.

That's not confirmed. Only about 93% of people who ever lived died so far.

So...

Did I get it right?

Depending on what you're treating, 50% sounds pretty good.

I remember when I went for my last surgery and I was signing all the consent forms, my doctor was emphasising the 17% chance of this known lifelong complication, and the increased 4% chance of general anaesthesia fatality (compared to 1 in 10,000 for general public).

My mum was freaking out because when she had the same surgery she'd been seen much earlier in the disease process, she wasn't expecting such a "high" risk of complications in my care.

But all I was hearing is that there's an over 80% chance it will be a success. Considering how limited and painful my life was by the thing we were treating, it was all no brainier, I liked those odds. Plus my condition is diagnosed 1 in 100,000 people, so how much data could my surgeon really have on the rate of risk, the sample size would be laughable.

Still the best decision of my life, my surgeon rolled his skilled dice, I had zero complications (other than slow wound healing but we expected and prepared for that). I threw my crutches in the trash 2 years later, and ran for the first time in my life at 27 years old after being told at 6 years old that I'd be a full time wheelchair user by 30.

That's awesome. I'm glad everything went so well. Here's to a healthy and long life! Even the idea of going under is terrifying to me. You definitely had some courage with that attitude and that's really admirable.

the gambler's fallacy is the opposite of what applies to #1

"is the belief that, if an event (whose occurrences are independent and identically distributed) has occurred less frequently than expected, it is more likely to happen again in the future (or vice versa)." -per wikipedia

#2 is an optimist? A glass half full type of guy maybe.

#3 i'd guess is inferring that the statistics are based on an even distribution where the failures are disproportionately made up of by the same select few surgeons. or maybe that's #2 and the scientist actually know the theory of how the procedure works in addition to what #2 knows about statistics and distributions.

1 in 100,000 not 10,000 (anaesthesia deaths)

10 points to Gryffindor

Yay!

The mathematician is probably feeling fine because he is computing the conditional probability of survival (otherwise fuck no I am not taking a surgery that has a %50 chance of killing me, that is way too much).

Gamblers fallacy or law of large numbers...

law of large numbers does not imply gambler's fallacy

First 20 patients died until the surgeon learned how to do it, next 20 survived. Technically it's 50% survival rate

Depends on the sample size.

If it's just this guy doing it, then yeah.

If it's this guy who has done the procedure 20 times with 20 successes, and another doctor who sucks, who performed the procedure 20 times with 20 fatalities, that's different.

It's likely that the sample size is much larger than one or two doctors.

Yeah that's how "normal people" thinks here

Can somebody explain the difference between the mathematician and the scientist parts of this?

The normal person thinks that because the last 20 people survived, the next patient is very likely to die.

The mathematician considers that the probability of success for each surgery is independent, so in the mathematician’s eyes the next patient has a 50% chance of survival.

The scientist thinks that the statistic is probably gathered across a large number of different hospitals. They see that this particular surgeon has an unusually high success rate, so they conclude that their own surgery has a >50% chance of success.

Thanks. I suspect a mathematician would consider the latter point too though.

Mathematician sees each individual outcome as independent 50% chance.

Scientist realises that the distribution of failures and successes puts him in a favorable position. e.g. for the 20 in a row to be a success in a 50% fail rate that means the previous 20 were all failures or some similar circumstances where the success rate rose over time or similar polarization of outcomes in the sample data which places them above average odds.

Assuming X~B(20,0.5), that gives us a p-value of...

0.00000095367431640625

Time to reject H0!

You're assuming those 20 were the only ones. Zoom out.

I was thinking more a binomial proportion test with the available data ;)

Also, yep, "assuming" was a key part of the statement!

Plot twist: 50% of each individual patient survives. Hope you get lucky with which organs make it

The left 50% or the right 50%

Bottom 50%

yes

So mathematicians and scientists cannot be normal people?

no.

No, never.

That’s mean

Until vastly larger numbers of people get trained in Advanced Mathematics and Degree Level Scientific disciplines, the human norm will never be anywhere near Mathematicians and Scientists.

It's quite literally abnormal to be a Scientist or Mathematician.

Then again, so is being Homeless or an Olympic-level Athlete.

...How much is the total amount?

WIth or without tax?

Being taught Statistics at University was a real eye opener on this...